Design

1 Aug 2023

5 Min Read

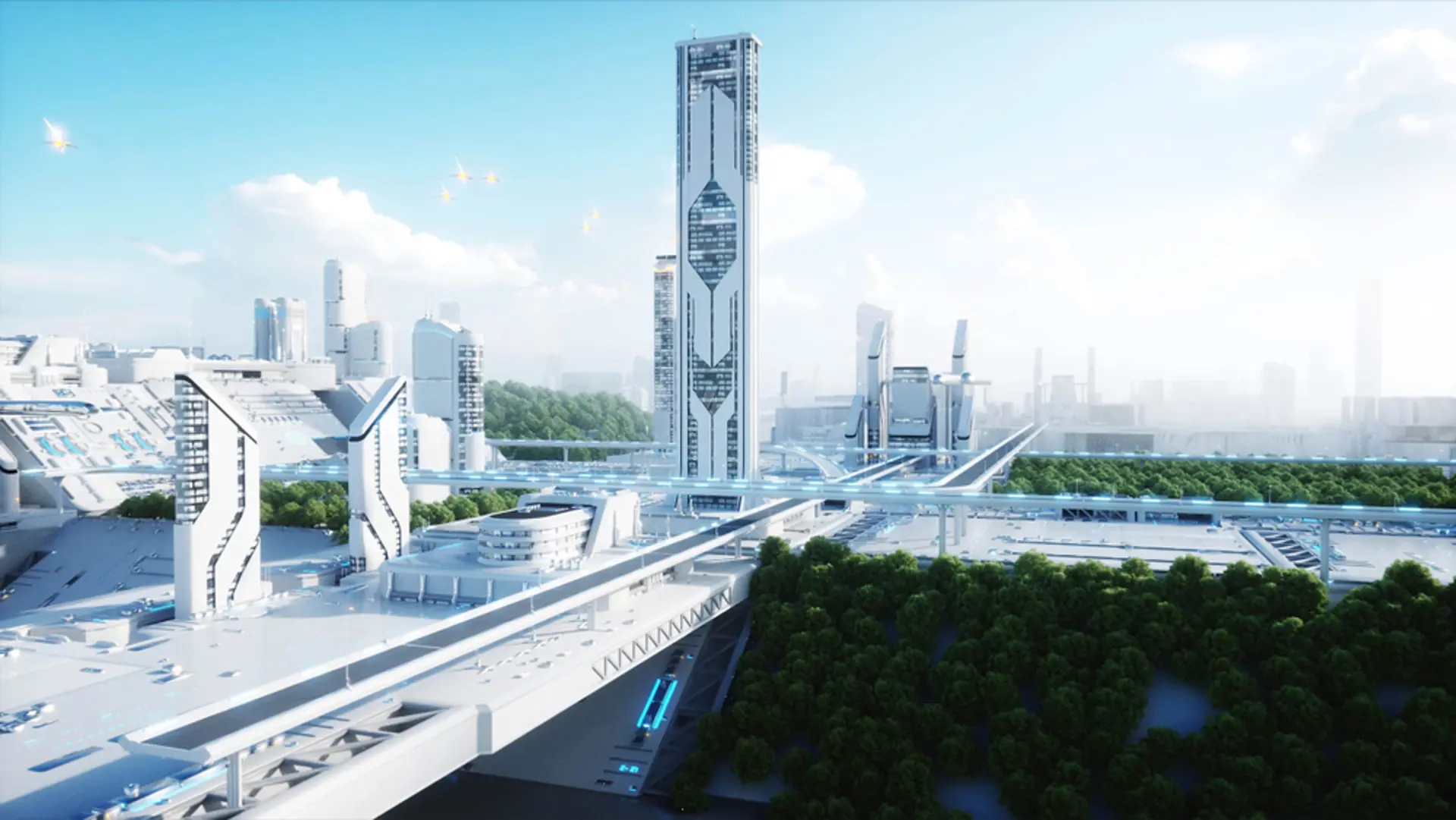

The Nature of Design: Biomimicry & Biophilia-Inspired Innovation

As the oldest innovator in the world, nature has had millions of years to perfect its design. Animals, plants and ecosystems have all had to adapt to changing environments in order to survive. Now, designers, thinkers and innovators from every discipline – even digital – must take inspiration from nature’s solutions, to design for a better future in intuitive, human ways.

“We’re blanketing ourselves in boringness, which sounds minor, but is actually a major mental health issue.”

Design