Tech & Innovation

1 May 2022

10 Min Read

Placemaking: Phasing In The Phygital

Now more than ever, communities, towns and cities are extensions of our innate drive to gather, to act as a group, to belong to a collective. Creating places that promote health, happiness and wellbeing is the ultimate task for urban designers who wish to build sustainably for the future. In our latest article, we explore how design, storytelling and digital innovation can build people-centred places that last lifetimes.

For millennia, people have sought to gather in environments that promote human to human interaction. From the forums of Ancient Rome and ceremonial sites like Stonehenge to modern day parks, bars, clubs and malls, humanity has always been innately driven to design places that create a collective energy; encouraging connection, camaraderie and cohesion – it’s perhaps why a cool draught beer in a lively pub garden trumps silently sipping a bottle on our back patios. Especially since the last two years have been smattered with seemingly unending periods of isolation for us all.

Now more than ever, communities, towns and cities are extensions of our innate drive to gather, to act as a group, to belong to a collective. Creating places that promote health, happiness and wellbeing is at the forefront of contemporary urban design. Pair this objective with rapid digital evolution and busy populations and modern placemakers have their work cut out for them, blending humanity’s complex needs and demands with effective, efficient yet non-invasive methods of making spaces feel like more.

When a City Becomes a Home

The concept of placemaking continues to be interpreted subjectively as time goes on.

Long understood by many to refer to the multi-faceted approach to the planning, design and management of physical public settings like parks and green areas.

For some, namely the Project for Public Spaces (PPS), placemaking is an art form. It is a collaborative, communal process whereby people create something new, beautiful, vibrant, and useful. The idea and sense of place tends to be steeped in collective meaning and significance. We form emotional attachments to places. They shape our identity and sense of self, and most importantly, they make us feel part of our communities.

Where it might seem, at first, like the ‘material’ being worked with is more tactile (concrete, trees, gravel, benches), what placemaking itself really creates is intangible: a social element that goes beyond physicality, as MIT's white paper Places in the Making explains:

“While the place is important, the ‘making’ builds connections, creates civic engagement, and empowers citizens—in short, it builds social capital. As architect Mark Lakeman of Portland’s City Repair organisation puts it, "the physical projects are just an excuse for people to meet their neighbours... The relationships that grow out of the ‘making’ are equal to, if not more important than, the places that result.”

Urban design, planning, and architecture may be effective, valuable tools for creating a physical environment, but it is the process of placemaking that creates the crucial, ephemeral quality—the sense of place—that ultimately animates any physical space, transforming design into destination.

Destination Design in Recent History

Urban planner Sir Ebenezer Howard OBE was an early pioneer of destination design and champion of biophilic living. Believing that overcrowding and deterioration of cities was one of the most troubling issues of his time, Howard imagined a utopian city in which people live harmoniously together with nature.

Specifically designed to reduce the alienation of humans and society from nature and provide the working class an alternative to working on farms or in crowded cities with a hybrid of town and country, his vision of the future became reality with the founding of the Garden City Movement. The first of which, Letchworth Garden City, was built in 1903, followed by Welwyn Garden City in 1920, with the movement influencing the development of several model suburbs in other countries around the world.

After World War II, Britain had high hopes for its new cities. Yet the flaws in places such as Stevenage, Cumbernauld and Crawley, constructed under the 1946 New Towns Act, intended to rebuild communities devastated by the war, were becoming apparent. The press identified the lack of social amenities and failure to mix classes as ‘new town blues’.

Then came Milton Keynes.

“Forged in the optimism of the late 1960s, a time of grand plans and technological leaps forward,” Britain’s fastest-growing new town has consistently been described as a “souless suburb” that has no place in the heart of Buckinghamshire. More recently, architects and urban designers have hailed “the elegant ambition of its original vision,” with city planners visiting for inspiration.

In 1960s North America, the placemaking movement simultaneously gathered pace. Said to have originated when American-Canadian journalist Jane Jacob and American urbanist William H Whyte began celebrating and designing cities that catered to people – focusing on the importance of livening up neighbourhoods and creating inviting public spaces, rather than emphasising automobile connectivity.

Present-Day Places

According to city planning expert Chris Choa, “cities are obsessed with understanding their own identity and potential in the world… They are interested in attracting new workforce and innovation that allows them to grow and prosper economically and socially.”

And post-pandemic, the power and attraction of cities remains. Why? “Because everything that makes a city attractive to viruses, makes it attractive to people and innovation as well. The cities that fared best are the ones that communicated transparently, that shared info across borders and cultures.”

Cities are inevitably the best environments for opportunities. They’re a hive of activity and, for a population who now flinch at the words ‘lockdown’ or ‘isolation’, activity is an irresistible magnet. Our cities also possess the frameworks to sustain our next steps, whatever they may be, and meet public demands for thoughtful spaces and ways of living.

Building Sustainably for the Future

The pandemic gave global consumers a new perspective on the climate emergency, with 71% of people agreeing that reducing their environmental impact or carbon footprint has become more important to them since it began. Institutions not baking environmental considerations into their recovery plans are being called out, and this is a valuable lesson for placemakers rebuilding for the future.

Many of the perceived environmental benefits that emerged from the COVID-19 crisis (decreases in carbon emissions, local air quality improvements, etc.) were accidental and unanticipated outcomes, joining an already growing appetite for walkability, access to green space and safer city cycling,

Demand for reallocating public space to ‘active transport’ has been felt particularly strongly in Italy (84.2%) and Spain (83.2%) and more moderately in Germany (64.1%) and France (76.1%), with consumers now looking to brands, developers and leaders to show willingness towards making some of the unintended environmental benefits of coronavirus more permanent features of places.

The mayor of Athens, Kostas Bakoyannis, is one of several city leaders who has ambitious plans to allocate 50,000 square metres of public space for cyclists and pedestrians: “We have this once-in-a- lifetime opportunity and are fast-forwarding all our public works[.] The goal is to liberate public space from cars and give it to people who want to walk and enjoy the city.” There are similar plans reported in Berlin, New York, Bogota, Paris, Sydney and London too.

Along with reallocation, regeneration projects are integral to sustainable urban development. Putting placemaking at the heart of such projects can ensure a legacy that endures beyond temporary events for long-term use in communities. Similar philosophies have been the blueprint for multiple major events, particularly in sports.

The London 2012 Olympics saw vast investment in East London’s infrastructure – one of the most visible being the creation of the Olympic Park itself on once-contaminated industrial land, supported by community education schemes on sustainable living – while the Paris 2024 committee have 95% of their venues either existing or temporary – evidence of their dedication to sustainability – with the only major construction project being their athlete’s village. Los Angeles 2028 is focused on a public transport system which will survive long after the games, providing a much-needed alternative to LA’s preference for private cars, and Brisbane 2032’s legacy is yet to be defined. Who knows, they could be the first digitally-driven games.

Unlocking Better Human to Human Interactions With…

Design

Changes in the way we work, travel and interact reveals that expectations for our environment have shifted. In recent years, calls for cities to focus on health in their planning are growing, with a new focus on access to greenspace and the quality of local greenspace as a key spatial justice issue.

“For the resilient, sustainable cities we all want and need, urban plans need to be designed, evaluated and approved using a health lens” Layla McCay, Director of the Centre for UrbanDesign and Mental Health.

When designers think about health, there can be a tendency to fixate on the physical over the mental. More and more, however, placemakers are visualising at the intersection of the two and creating spaces that promote well-rounded healthy lifestyles for everyone. In Vancouver, the government has implemented a ‘Healthy City Strategy’ that sets out various goals for urban design including: ensuring 18% of the city’s area to be covered by tree canopy and all residents to live within 400 metres of a park or green space.

From a safety perspective, Singapore has integrated a network of roads, trains, buses and taxis as part of its Walk, Cycle, Ride initiative, which makes it easier for citizens to combine multiple modes of transport, encouraging more liveable recreation spaces and more active lifestyles while promoting sustainable energy use.

Further adaptations to city design include leveraging artificial intelligence (AI) to ensure safety and security for citizens while safeguarding privacy and fundamental human rights, adopting circular models based on a healthy circulation of resources, and on principles of sharing, reusing and restoration.

As seen in Cambridge, the “15-minute” city is also gaining traction, designed in a way that amenities and most services are within a 15-minute walking or cycling distance, creating a new neighbourhood approach. Other urban negotiations also concern themselves with pedestrian movement: a full-scale prototype of the Starling Crossing – a responsive road surface that reacts dynamically in real-time – has been installed in South London to generate a greater awareness of safety and each other among commuters, one of many urban design projects putting people first.

Storytelling

Strengthening the connection between people and place has always been the purpose of storytelling. History, heritage and legacy are huge components in our dynamic relationships with where we’ve settled throughout time, and creating and maintaining these narratives are key to placemaking.

Research project, Local Legends, sets out to define the value of narrative in placemaking, based on the notion that something as simple as a story can add immense value to our cities, landscapes and destinations. Learning from pioneering storytellers and placemakers uncovers how stories could be a superpower in building better places.

That’s not to say these narratives need to be forced or falsified.

“Stories in placemaking and architecture evoke strong emotions; we understand and connect with places through stories, describing not only the physical nature of a place but what it feels like to be there, how it is experienced.” Anna Howell, Senior Urban Designer

One of the more evocative examples of placemaking narratives surrounds Pittsburgh's City of Asylum, a project dedicated to transforming vacant properties into sanctuaries for writers exiled from their homes. Promoting safe places for expression has given rise to a thriving creative community, beautifully blending the stories of many into one narrative that gives a place purpose.

In London, the extensive redevelopment of Battersea Power Station is steeped in its iconic heritage. A dedicated app reveals the history of the Grade-II listed building, manifesting in a heritage trail, a game for younger visitors and an augmented reality experience allowing users to explore the building from its former glory to its modern magnificence.

Slightly further north lies Camden People’s Museum, a new concept of the word ‘museum’ with showcases spread across the Camden landscape in creative spaces that are easily navigated in an app and ultimately, to allow visitors to experience the “stories, sounds and spirit of one of London’s most iconic boroughs.”

The challenge for placemakers is how to dig deep to find a place’s genuine narrative whilst encouraging residents to contribute their own anecdotes to their place’s overarching story. How do you use content as a material to design and craft a new place that appeals to your audience and at what point do you invite those who belong there to make the story their own?

Digital Innovation

The first step in delivering a destination designed for tomorrow is understanding that our meaning of ‘place’ has changed. We no longer just inhabit physical spaces, but digital ones too: in 2020, we spent an average of 6 hours and 59 minutes online per day, created 2.8 billion communities on Reddit and spent $1.31bn on Roblox in the first 6 months of 2021.

Digital placemaking is the process of creating connections between people and the digital worlds they inhabit. It often focuses on helping people unlock more immersive experiences, cultivate and express their identity and find a sense of belonging with like-minded people online, but when a user’s physical and digital worlds start to speak to, and learn from, each other, the impact is unmatched.

Singapore consistently tops the charts for the smart and liveable cities. Its approach is simple: embed technology and digital innovation throughout the physical city in order to respond to its citizens’ ever-changing needs. Adopting this people-centric approach reduces the risk of failure and meets demands for our physical and digital worlds to overlap, collaborating to deliver smart, personal, integrated experiences across any touch point.

Uber. Spotify. Online Doctors. These are all integrated experiences that combine physical and digital properties to create a seamless, personal, useful experience that meets specific needs and solves specific pain points better than its physical-only predecessors. Integrated experiences happen on a spectrum. They can be functional solutions to everyday problems like accessibility or way finding. Or they can be artistic and creative moments that spark delight and wonder.

Again, take Singapore as an example. Digitising the healthcare system made it easier for Singapore’s ageing population to access face-to-face patient care through their smartphones, creating a healthier city and healthier citizens. AI chatbots were created to talk to the elderly in a bid to reduce loneliness and isolation by facilitating ongoing conversation and sharing relevant community events.

Through Singapore’s Smart Nation app, citizens can report municipal issues, receive location-specific environmental alerts on air quality, temperature and rainfall and access information tailored to young families and elderly residents.

Approaching innovative placemaking in a more creative, emotionally-connective way, Minneapolis installed a 40’x75’ inflatable ‘collective mood ring’ that changed minute-to-minute according to the real-time moods of Minneapolis’ Twitter users in order to encourage meaningful connection and conversation in an under-utilised park.

In the UK’s most playful city, Playable City Bristol was the launchpad for Watershed’s global vision. Putting people and play at the heart of the future city with smart technologies that cultivate connections, the programme linked innovators from all over the world with one goal: to playfully rethink public space and experiment with digital innovation to infuse fun and meaning into them.

One project, Urbanimals, saw origami-like creatures projected onto surfaces across the city. Using motion sensors to trigger the projections, locals found themselves visiting previously unexplored areas of the place they call home in a Pokemon-Go-esque hunt for cute digital creatures and instead finding a newfound appreciation for their urban landscape.

Urbanimals, Bristol, UK

Urbanimals, Bristol, UK

Integrated Placemaking

The meaningful places of the future will also de-silo the digital and physical. Already, we see that many digital places have elements of physicality and physical spaces are embedding elements of digitisation. Coined ‘integrated placemaking’, it allows the owner of a place or technology to have ongoing communication with residents, which makes it easy to influence future actions and create new behaviours.

There are four tenets through which we create an Integrated Place:

- Discovery: helping people explore and understand what the space is, and all it has to offer them.

- Engagement: provoking meaningful interactions between the user and the space.

- Individualisation: allowing individuals to have tailored experiences within the place based on their unique identity, needs, drivers and challenges.

- Connection: cultivating a sense of civic meaning and belonging to the place.

A good example of integrated placemaking in action is Pavegen’s hi-tech tiles, which generate electrical energy by being walked (or danced) on. When distributed around an urban environment, residents and visitors can download an app to see how much energy they’ve created for the city. Additionally, once downloaded, the app will notify users whenever they’re close to Pavegen tiles, incentivising newly climate-wary consumers to contribute to sustainable energy sources in an easy, innovative and fun way.

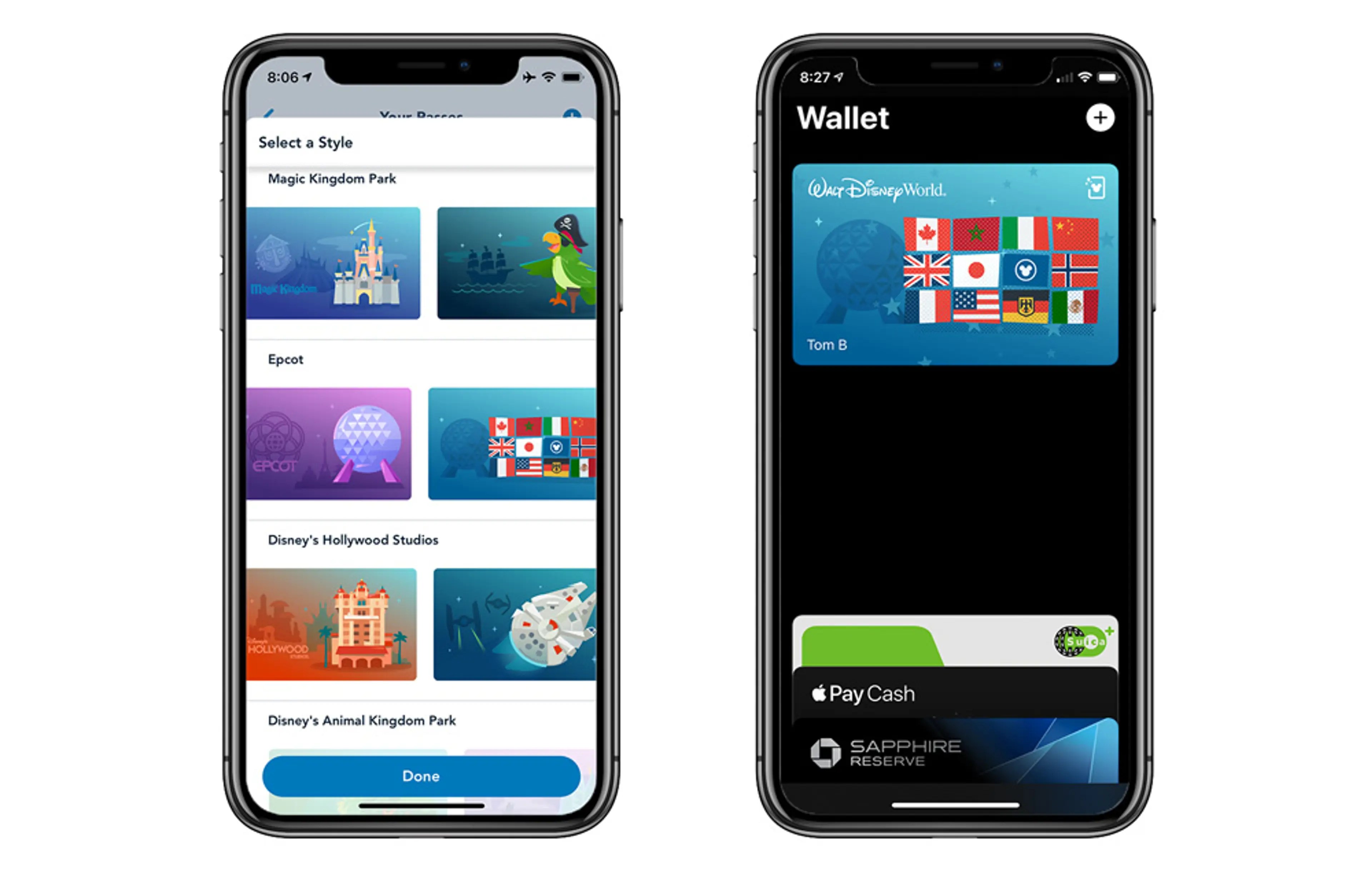

Speaking of fun, Disneyland has constructed an integrated place that creates ground-breaking customer experiences by using innovation and technology to meet visitor needs, solve pain points and create the next iteration of magical Disney moments.

Functional tech such as Magicbands and Magic Mobile allow for seamless transactions and easier navigation – key in such a large resort, while the Disneyland app allows visitors to explore the park and plan out their visit before they arrive. In-app ride booking abolishes the age-old problem of queuing for rides, with the collected data allowing the conglomerate to tailor future experiences for guests and improve the physical park design and traffic flow.

While seamlessly integrating digital worlds in our physical spaces supplies unparalleled potential in these arenas, it brings with it a number of obstacles to navigate.

Key Benefits & Challenges Faced by Placemakers

Key Benefits for Public and Private Organisations:

- Higher Investment: The more meaningful a place is to us, the more time and energy we invest into it.

- Community Ownership: Collective investment in these spaces will breed a shared sense of ownership as they become communities, eliciting a linking element of care for the place.

- Longevity: Meaningful places are more likely to attract and retain groups of people over long periods of time.

- Economic Development: Creates higher real estate values, higher occupancy rates, increased tourism and more job and business opportunities.

Key Challenges for Public and Private Organisations:

- Finding The Balance: According to a survey by Four Communications, placemakers feel their biggest challenge now is planning for the long-term as well as handling immediate issues.

- Staying Current: Consumer behaviour will fluctuate forever, with more and more people globally using food delivery services, exclusively shopping online, working from home and more, brands will need to be adapting to solid shifts without getting caught in temporary trends.

- Setting Boundaries: Achieving optimal tech integration without being invasive will be one of the initial priorities for placemakers as the physical and digital worlds merge more and more.

- Future Shocks: We’ve already seen vast change in a relatively short span of time in terms of global shifts. Leaders should aim to build places that are resilient to any future circumstances or at least set out solid frameworks for recovery.

Placemaking Is Going Places

Where to next? Chris Choa predicts that, in the long term, “there will not be that much difference in structural changes of cities. The core will remain the same and the concentration of people will continue.” People are attracted to other people, a pull only exacerbated by the pandemic.

On the other hand, short-term change is occurring in the sense of lower building density, as well as exposure to light and air. To achieve this, “cities are not going to tear down existing builds but repurpose what they already have.” A good example of this is Milan, which, after pivoting road and parking space for pedestrian use during the pandemic, is talking about keeping these changes in place, now that the virus has subsided.

Digital innovation and technological advances are an ongoing, underlying structural change to cities and will continue to be so, the hybrid between physical and digital worlds driving value and ensuring that cities continue to be an extraordinary force.

Maybe experiences in work and leisure will become as immersive as some of the world’s high-tech high streets, morphing into places where we can stumble across ideas we haven't had in static spaces. Or perhaps every aspect of our existence will become digitally enlivened, a future that may feel almost dystopian to some but entirely within reach for others. Whatever it holds, placemaking will always be a noble pursuit as long as it’s done with communities, not to them.

If you'd like to discuss how we partner with timeless luxury brands to provide brand strategy, digital experience design and innovation consultancy, please get in touch via [email protected] to arrange a time to speak with our team of consultants our services.

Design

Hospitality & Travel

Brand & CX

Tech & Innovation